I genuinely don’t know what I expected before coming here, and yet I have a sensation of having been proven wrong. Perhaps the most difficult part of this trip is to write about it without sounding like I’m being fictitious and making things up. Because there are aspects to life you never really come across anywhere but the places that are a bit off the normal grid. And Uzbekistan is of course no exception. This showed from basically the moment we stepped foot on Uzbek soil. Actually, it started before that. Upon making our booking for a hotel, we were informed to bring a marriage certificate to show at the hotel… what else could be expected in such a stronghold of tradition? In lack of said certificate, we decided to cross that bridge when we got there. Or sleep under it if it came to that. Luckily, this was never necessary, even though there was a point when there seemed to be no hotel at all.

Our trip started like you’d think it would. The driver who came to pick us up from the airport informed us that “unfortunately” our booked hotel was fully booked (?) but “fortunately”, he knew someone who knew someone who runs another hotel, and we could stay there for “almost” the same price. Well, it’s just not the kind of mishap you want to encounter in the middle of the night in a country where next to no one speaks English. There are moments in life when you should just close your eyes and say “yes”, but this didn’t feel like one of them, so with a little persistency, we did make it to our intended hotel in the end. If we dodged a bullet or not we’ll never know, but some of the ”furniture” in the lobby were literally bales of hay covered with blankets. I don’t know if that’s standard for a boutique hotel in Uzbekistan?

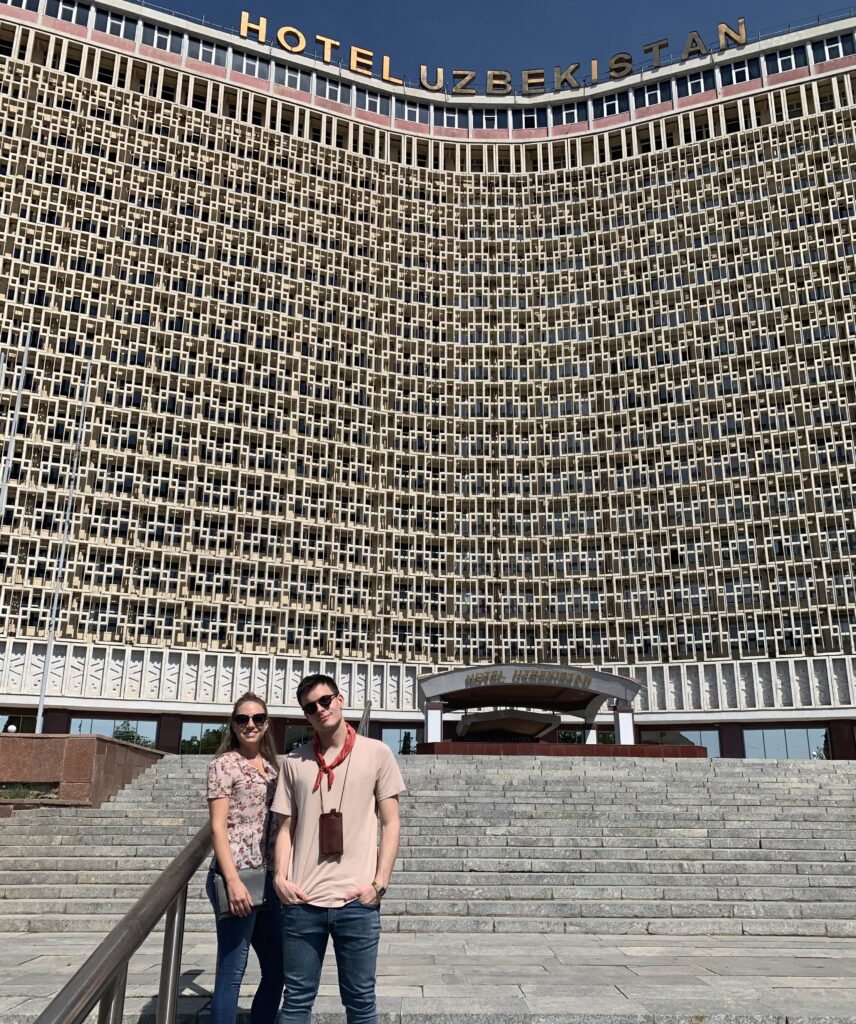

Tashkent is an unusual capital. Whenever I find myself in a new place for the first time, I always try to imagine that if I were to wake up here with no idea of where I was, what elements would tell me I’m not at home anymore? This has opened my eyes to details I otherwise wouldn’t have noticed. At first glance, it seems like globalization has completely bypassed this city. And I’m not only saying that due to the absence of western signs and logos. The city somehow feels both small and grand at the same time. It’s something with the scarcity of skyscrapers and towering buildings and the impressive remnants of the Soviet era that does it. The buildings are tiny, but the many avenues are wide. The streets are lined with oak and chestnut trees shadowing over the broad sidewalks, which makes it a pleasant city to discover by foot, even under the sweltering sun. Immense parks are laid out everywhere, and an elaborate irrigation system keeps the city green. Even though it’s only spring, it almost feels like the air stands still during most parts of the day. The heat soars to a merciless 60 degrees during the peak of summer. For this very reason, we are told, the most expensive apartments to buy are always the ones on the lowest floors as they withstand the heat the best. Many of the old Soviet buildings are dilapidated, but still captivating in what they represent; the contrast between the awesome exteriors and the stark realities that lived behind them. The cousin of a friend takes us around one morning, and she was not equally impressed. “Inside, they all look like prisons”. That’s not a coincidence, apparently, the same architecture also designed many Soviet prisons. The markets and bazaar are a dream for an overseas visitor, with price levels for the locals. The cousin points to a table of Channel bags and Louise Vuiton wallets and says: “Here you see what’s left of the Great Silk Road”.

The metro is an attraction in itself. It’s quite a contrast to descend from the occasional disarray above ground into the art exhibition every metro station holds. The platforms are marbled and dotted with ornamented columns, all lit up by chandeliers. It was prohibited to take photos in the metro until recently, but as the country is becoming more open, this has changed. And it’s good that it’s working so well because the traffic is not for the fainthearted. I barely know where to begin to explain why not… The white markings dividing the lanes are faded beyond recognition on many roads, basically turning them into massive single lanes. Here and there are opening in the center barrier to allow drivers to do a u-turn in the opposite direction, however, since 3 or 4 cars normally try to do it at the same time, this isn’t always ideal. Of course, there are no red lights. And seatbelts in the cars? Forget it. At one point I exclaimed: “They really should put up signs for these speeds bumps!”, and the reply was: “That’s not a speed bump, it’s just the road”. There is also some uncertainty whether being a taxi driver in Uzbekistan is an actual profession, or if it just means that you access a car?

However, the biggest reward of coming here has been the people we’ve met. Everywhere we’ve gone we’ve been meet with kindness and curiosity. And something as rare as genuine interest. Even if very few people speak English, they’ve wanted to know who are and why we decided to come here. It’s been a reminder that language is just one of many ways to communicate. This kind of treatment you’d never get in a place that sees a lot of tourists, which is an appeal in itself. One evening we had the privilege of being invited to our mutual friend’s mother’s birthday party. Anyone can book a plane ticket and go wherever they want to go, but you need an invitation to take part in someone else’s culture, and that’s what makes it so special. And it was special. I could go into detail about all the home-cooked food, the (of course) home-brewed beer, or the many vodka shots (not sure if home-brewed), but my strongest memory will be of something else entirely. Something that caught me by surprise. And that was the intimate bond all of these people seemed to share. Even if I met them all for the first time and had difficulty communicating with the majority of them, it was obvious how close they all were. They had shared and followed each other’s lives and milestones, and this showed in subtle things like how gently they laid hands on one another, how they bickered, and how they laughed like you can only do with people you truly know. I sometimes wish I could switch off my brain and just enjoy myself at the moment instead of analyzing my surroundings, but it felt like such a privilege to have been invited into such a tight-knit group. Whenever someone called it a night, the entire entourage stood up to walk them out and wave them off, and I’ve never seen anything like that. Standing right there, on a dirt road far out in the Uzbek countryside, with cows lowing in the background and Russian classics blaring from a stereo, it made me think of what an immense contrast it all is between this reality and the one I come from, in a western society.

So often we sit there on our high horses claiming to be so progressive and open-minded, but when did you attend a party the last time when all 20 guests came out to wave you off? It’s difficult not to wonder where the middle ground is between tradition and progression? Where do we find the balance of the tradition of sticking together while keeping our hearts open enough to accept everyone for who they were born to be, what choices they make, and the opinions they hold? I know people who sacrificed their families to be able to be themselves. I know people who sacrificed being themselves to have their family. What’s the bigger price to pay? Of course, in a perfect world, you shouldn’t have to pay at all. We all have so much to learn from each other, which is why meetings between cultures are so important.